Chapters

- Risk/Leverage Ratios

- Profitability Ratios

- Valuation Ratios

- Activity Ratios

- Liquidity Ratios

- Understanding Financial Ratios

- Understanding Cash Flow Statements

- Understanding Income Statements

- Understanding Balance Sheet

- Understanding Financial Statements

- Basic Terms In Fundamental Analysis

- Steps In Fundamental Analysis

- Introduction

- Study

- Slides

- Videos

7.1 Understanding Cashflow Statement

Statement of cash flows, which, as its name implies, summarizes the sources and uses of cash during the period and computes the net change in the cash (and cash equivalents) of the firm. Each entry in the statement of cash flows is classified into one of three categories:

-

Operating activities: Cash flows related to the primary business function of the company.

-

Investing activities: Cash flows resulting from the purchase or sale of long-term assets (e.g. plant, property, equipment).

-

Financing activities: Cash flows related to the financing operations of the company (i.e., bank loans, bond issuances, sale or repurchase of stock, etc.)

The sum of the cash flows associated with these three sources, plus any adjustments due to changes in exchange rates, gives the net change in cash in the period.

The purpose of the statement of cash flows is to give investors an indication of the firm's liquidity, that is, its ability to meet its financial obligations, particularly in the short-term. While many of the items in the balance sheet and income statement are not "real" insofar as they represent additions or subtractions from income, assets, or liabilities stipulated by accounting conventions (e.g., depreciation and amortization) and not actual payments, the statement of cash flows focuses on the most liquid and tangible asset possible, the firm's cash position, and therefore provides a more accurate picture of the company's ability to continue operating.

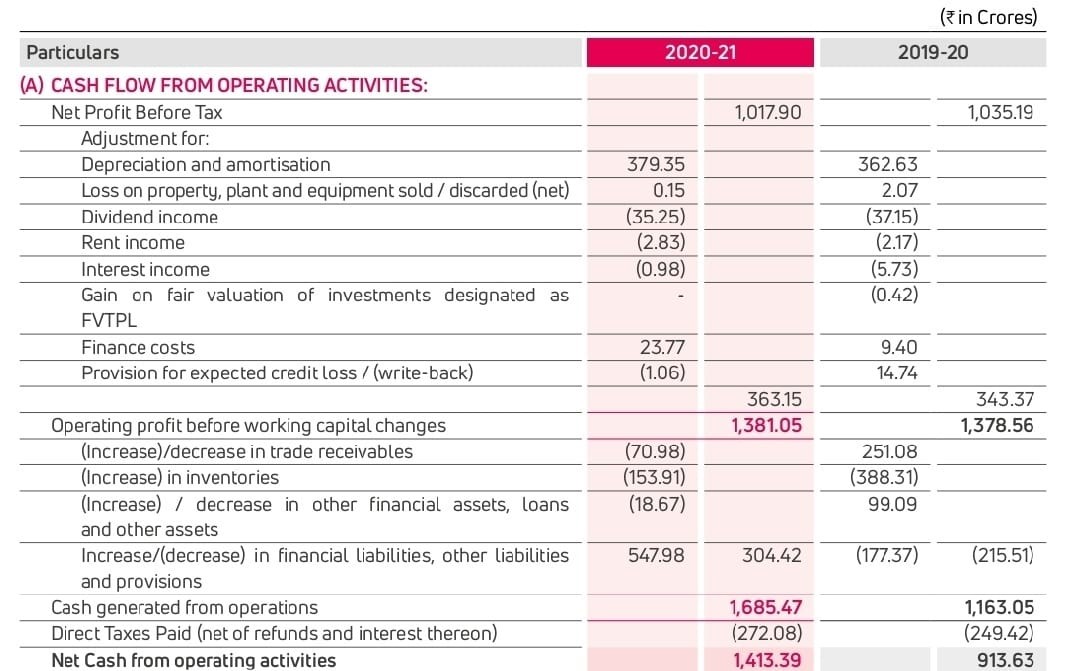

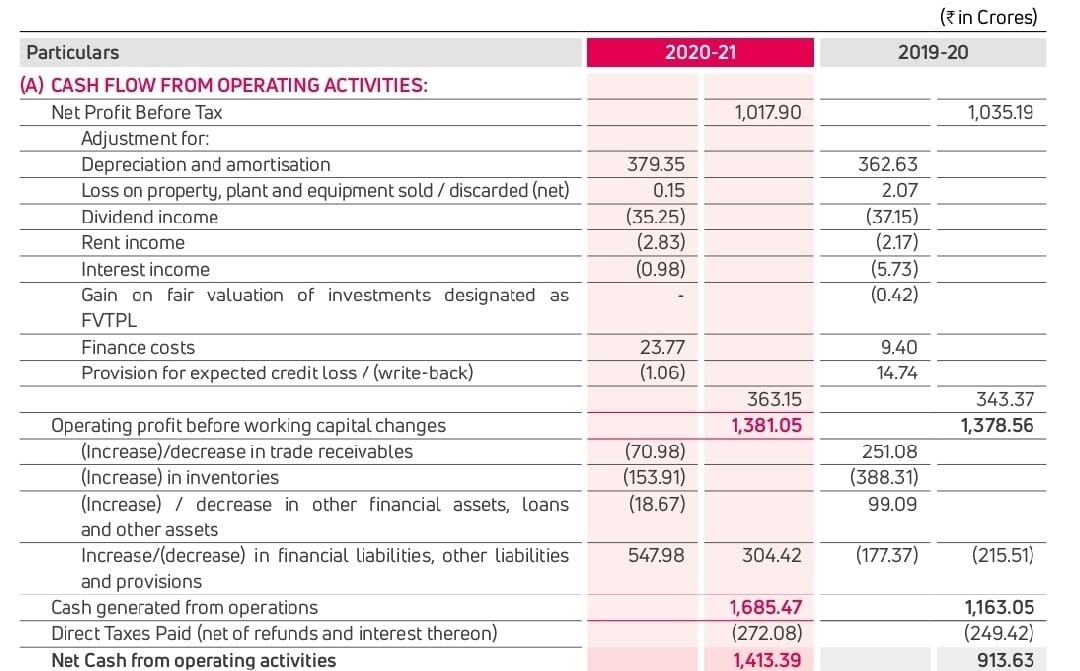

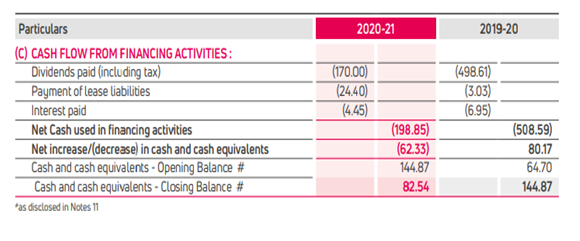

A sample statement of cash flows for Exide Industries is shown below: -

7.2 Cashflow From Operating Activities

Cash flow from operating activities- It is the section of a company's cash flow statement that represents the amount of cash a company generates (or consumes) from carrying out its operating activities over a period of time.

To calculate the cash flows from operating activities, we begin with the net income, the final calculation of the money earned by the firm as computed on the income statement. Since our interest is in the operating activities only, the first step is to subtract from the net income, the non-operating income (also taken from the income statement) to isolate the net income from operating activities. (Because it is a source of cash for the firm, the non-operating income will be recognized elsewhere on the statement of cash flows, either in financing activities, investing activities, or partially in both.) The next step is to convert the net income from operating activities into the net cash flow from operating activities by backing out all the noncash forms of revenue and expenses.

-

Depreciation and amortization: There is no actual cash outflow associated with the depreciation of an aging asset or the amortization of the cost of an intangible asset. This is simply an accounting adjustment made to the income statement to align revenues with expenses. Therefore, the loss on the income statement from depreciation and amortization is added back in

-

Changes in operating assets and liabilities: The starting point for the statement of cash flows is the net income, taken from the income statement, which represents the total revenue of the company that can be transferred to shareholders' equity or paid out in dividends. By the balance sheet identity Assets - Liabilities = Shareholders' equity, the net income represents the change in the total assets and liabilities of the company. What it does not tell us is how the composition of the assets and liabilities has changed between cash and noncash items. In this section of the statement of cash flows, the cash balance of the firm is adjusted for changes in the composition of the current assets and liabilities. (Changes in non-current assets and liabilities are generally recognized in the cash flows from investing and financing activities, which we will see shortly.)

Formula- Cashflow From Operation= Net Income+ Non-Cash items+ Changes in working capital

Snapshot of Cashflow from Operating Activities:

The general rules are that:

-

A decrease in a noncash asset is a source of cash while an increase is a use of cash. For example, a decrease in accounts receivable implies that payment was received, which increases the cash balance.

-

An increased liability is a source of cash while a decreased liability implies cash was used to pay down the obligation and therefore reduces the cash balance.

All of these changes in the current assets and liabilities can be computed by comparing the composition of the balance sheet to that of the previous accounting period.

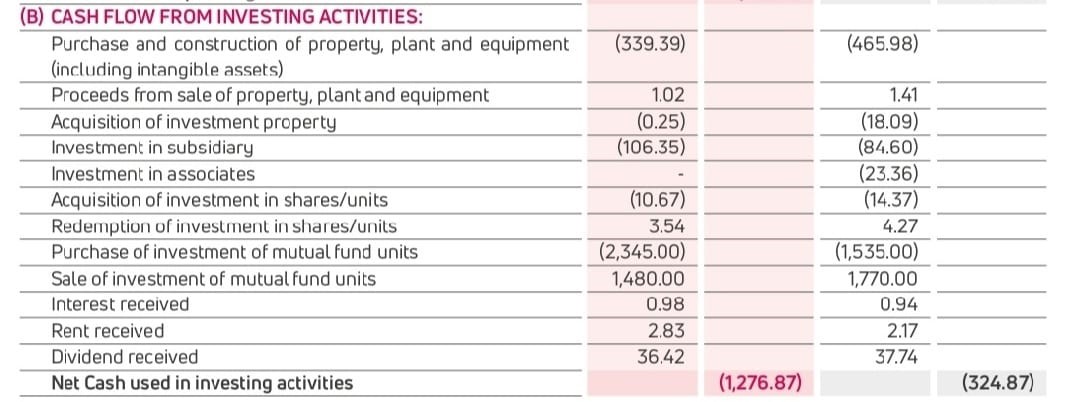

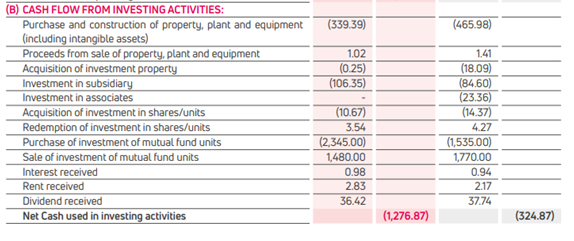

7.3 Cashflow From Investing Activities

Cash flows from Investing activities: The cash flows classified as resulting from investing activities are those that relate to the acquisition or sale of long-term assets. These may be the sort of tangible assets classified under Plant, Property, and Equipment on the balance sheet, as well as the acquisition of other companies or any other long-term investment. Many of the major items here would be visible from the changes in long-term assets on the balance sheet from the previous period.

7.4 Cashflow From Financing Activities

Cash flows from Financing activities: The term financing activities broadly includes any of the interactions between a company and either its creditors or shareholders. This includes cash flows associated with the sale of shares to the public, a stock repurchase by the company, the issuance or repayment of debt, the receipt of a bank loan, or the payment of dividends on either preferred or common shares. Financing activities will often be visible from the changes in the composition of the shareholders' equity on the balance sheet.

7.5 Free Cash Flow

One of the most important values that is calculated from the statement of cash flows is the free cash flow, which measures the cash raised in the period that could either be retained by the company or paid out to shareholders as a dividend. It is calculated as the cash raised from the pursuit of the company's primary business, less what was actually spent on new fixed assets (actual expenditures, not depreciation and amortization) less what has already been paid out in the form of dividends to all holders of equities.

Free cash flow = Cash generated from operating activities - Capital expenditures

Many analysts focus on free cash flow as a superior measure of economic performance to net income due to the fact that net income is more easily manipulated through accounting adjustments, while cash flow is more objective. While a company with strong free cash flow generation is in a position to expand their business without need for additional financing, this does not mean that significant positive cash flow is necessarily good or that low or negative free cash flow is bad. A company that generates a great deal of free cash flow but does not employ that cash to productive ends may be a much less attractive investment than a company with negative free cash flow due to large investments in capital goods that will produce significant returns in the future.